|

MARTIAL MUSINGS

North Leg South Fist

A Brief History of Chinese Martial Arts

Conflict has been an element of human existence since the dawn of time, stemming from reasons as diverse as disputes over food resources to control over national boundaries. Martial Arts were born as a way to minimize unpredictability in combat, to give the practitioner an edge over someone with inferior training. While martial forms began as a means of increasing the effectiveness of armed combat, they later extended into the realm of unarmed fighting. This pattern mirrors martial history in China. Throughout ancient Chinese history, references are made to famous warriors and their weapons; to beautiful but deadly sword forms; and a myriad of exotic weaponry.

The Founder of the Shaolin Temple, Da-Mo

|

It was not until the 7th Century that texts start mentioning unarmed combat. It was around that time that Indian Buddhist Monk Da-Mo came to the Shaolin Temple in Henan Province, China, and taught the Monks there body conditioning exercises. In addition to the Shaolin martial arts that flowered there, other indigenous styles centered around Wudang Mountain and O-Mei Mountain developed their own unique flavors. As these various arts evolved and branched off, the number of fighting systems grew exponentially. Today, hundreds of styles exist in China, with new ones constantly being born.

North & South, Internal and External

So how does one categorize all these styles? Generally speaking, Chinese martial arts are broadly classified by their place of origin and their structural characteristics. By origin, we divide styles into Northern and Southern; by structure, we differentiate in terms of External and Internal.

When defining a particular type of Kung-Fu by location, the Yangtze (Changjiang) River serves as an arbitrary border between north and south. The well-known folk saying “North Foot, South Hand” presents a general summary of the differences between Northern and Southern styles. In North China, where people tend to eat wheat over rice, body types tend to be taller and thinner. Therefore, stances tend to be higher and long-range kicks and punches take precedence over in-fighting techniques as demonstrated by styles such as Long Fist (Chang Quan), Wheel Boxing (Fanzi Quan), and Arhat Fist (Lohan Quan). On the other hand, in the South, where people tend to be shorter due to the staple rice diet, the stances are usually low and short-range hand techniques are more prevalent over longer kicks. Further, the boat cultures from which several southern styles emerged necessitate low and stable stances for use in choppy waters. Arts like Hung Gar, Chow Gar, and Bak Mei all share these similar characteristics.

Taiji's Single-Whip (demonstrated by Johnny Jang, courtesy of O-Mei Academy in Oakland, CA)

|

In opposition to the arbitrary division of styles by North and South, Internal and External styles present a somewhat more clear differentiation. External styles clearly embrace the rapid development of physical strength and speed. Forms tend to be energetic and the techniques within have clear martial application. On the other hand, Internal arts seem more meditative in nature, and depend on a gradual development of explosive power. Some famous internal styles include the many families of Taijiquan (Tai Chi), Bagua Zhang, Xingyi Quan, and Liu He Ba Fa (Water Boxing).

While these vague categories group styles according to their characteristics and origins, they do not always accurately reflect the diversity of Chinese martial arts. Some northern styles like Shuai Jiao (Fast Wrestling) prominently use in-fighting techniques, while some Southern forms like Choy Lay Fut have strong long-range skills. Furthermore, Kung Fu styles like Mizong Quan from the Jiangzhe region between North and South embody characteristics of both. With regards to structural characteristics, a martial adage says “External trained over a long time becomes Internal; Internal trained over a long time becomes External.” That is to say, External stylists may eventually develop the explosive power characteristic of Internal arts, while Internal practitioners may gain the clear, practical applications typical of External forms. At the same time, many Internal styles like Bajiquan have clear external motions while External arts like Wing Chun Kuen contain evident internal characteristics.

Imitation Styles

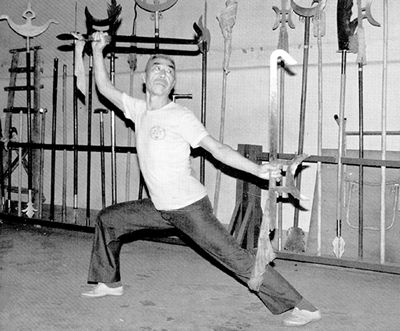

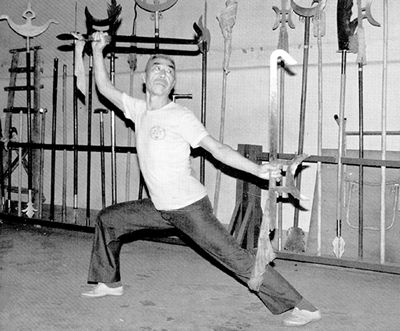

Kao Desheng of Taiwan taught Northern Mantis

|

In addition to the aforementioned categories, several styles imitate the movement of animals. Created with the assumption that animals had more natural fighting skills than humans, these Imitation Styles attempt to imbue their practitioner with animal characteristics. The ferocity of the Tiger, the grace of the Crane, the tenacity of a Mantis, or the guile of the Monkey allow the practitioner to surpass the physical limitations of the typical man. Hundreds of these styles exist and provide a unique flavor to Chinese martial arts. While generally external in nature, they can be seen in both Northern and Southern Kung Fu.

Standardization in Modern Wushu

Former Beijing Wushu member, Li Jing (courtesy of Adam Tow, http://www.tow.com)

|

Since martial artists throughout Chinese history have been at the forefront of dynastic change, the practice was banned by the Communist Party after their rise to power in 1949. Later realizing the popularity of fighting arts around the world, China’s leadership sought to establish itself as the mother of martial arts. However, it did not want “comrade fighting comrade,” and therefore sought to make competition more performance based. Today, many old forms from many different styles have been standardized and their technical difficulty increased. While martial application is often not emphasized, training develops speed, flexibility, strength, endurance, and explosiveness.

Further, China has since adopted standardized rules for full contact sparring, incorporated into the concept of San Shou. Fought on a raised platform called a lei tai, San Shou incorporates the major elements of Chinese martial arts: punching, kicking, throwing, and joint locking.

With the former poised to become and Olympic event, the growing popularity of the latter, and the rich diversity of traditional styles, Chinese martial arts has a lot to offer and a lot of room to grow in popularity.

|

FAQ

|